‘Astrophysics for People in a Hurry’ presents an introductory overview of a rather complicated science. Neil deGrasse Tyson weaves a masterful tale of space and time into this small volume, giving us a history of his chosen profession along the way.

Far from dry and boring, his descriptions of the various elements of interest to the astrophysicist read like the biographies of actors in a star-studded cosmic saga, rather than a mere overview of the periodic table.

Additionally, Tyson expounds on the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy; light and magnetism, and how the measurement of these allows us to peer into the universe. He gives us a sense of cosmic scale—ranging from individual molecules which form the building blocks of everything we know, to the massive expanse of the observable universe.

Tyson’s enthusiasm for his craft reveals itself throughout the book, becoming quite contagious as he recounts the stories of various ‘accidental’ discoveries which enabled his branch of science to reach its present sophistication.

Our natural ability to observe the universe is limited. The use of optics began to expand this ability—just as the microscope enabled Van Leeuwenhoek’s discovery of single-celled organisms, the telescope allowed for the observation of stars and galaxies previously invisible to the naked eye. Until 1800, however, the scope of our sky-peering was limited to visible light. In that year, English astronomer William Herschel began experimenting with prisms.

Prisms have been used to divide light into its component colors for hundreds of years—in the 1600s, Sir Isaac Newton used one to establish that the seven colors of the visible spectrum are red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Herschel’s idea was to measure the temperature of each individual color to see if there was any variation across the spectrum. To do this, he placed thermometers at the appropriate locations along the rainbow, as well as a thermometer outside of the spectrum, adjacent to red—he needed to measure room temperature so that he could compare the other measurements against a control.

As he suspected, different colors registered different temperatures. Much to Herschel’s surprise, however, his control thermometer rose even higher than red—indicating the presence of something outside of the visible light spectrum. He had discovered a new band of light—infrared light.

Others built upon Herschel’s experiments, and in 1801 Johann Wilhelm Ritter discovered another band of invisible light adjacent to violet on the spectrum—ultraviolet light.

Bell Labs accidentally contributed to two additional advances in the mid 1900s—the discovery of radio waves emitting from the Milky Way galaxy around 1930, and the discovery of the ‘cosmic microwave background’ in 1964. These accounts benefit from Tyson’s masterful storytelling, so I’ll let you discover them in the book.

I’ll close with a quote from the book on the importance of perspective:

During our brief stay on planet Earth, we owe ourselves and our descendants the opportunity to explore—in part because it’s fun to do. But there’s a far nobler reason. The day our knowledge of the cosmos ceases to expand, we risk regressing to the childish view that the universe figuratively and literally revolves around us. In that bleak world, arms-bearing, resource-hungry people and nations would be prone to act on their “low contracted prejudices.” And that would be the last gasp on human enlightenment—until the rise of a visionary new culture that could once again embrace, rather than fear, the cosmic perspective.

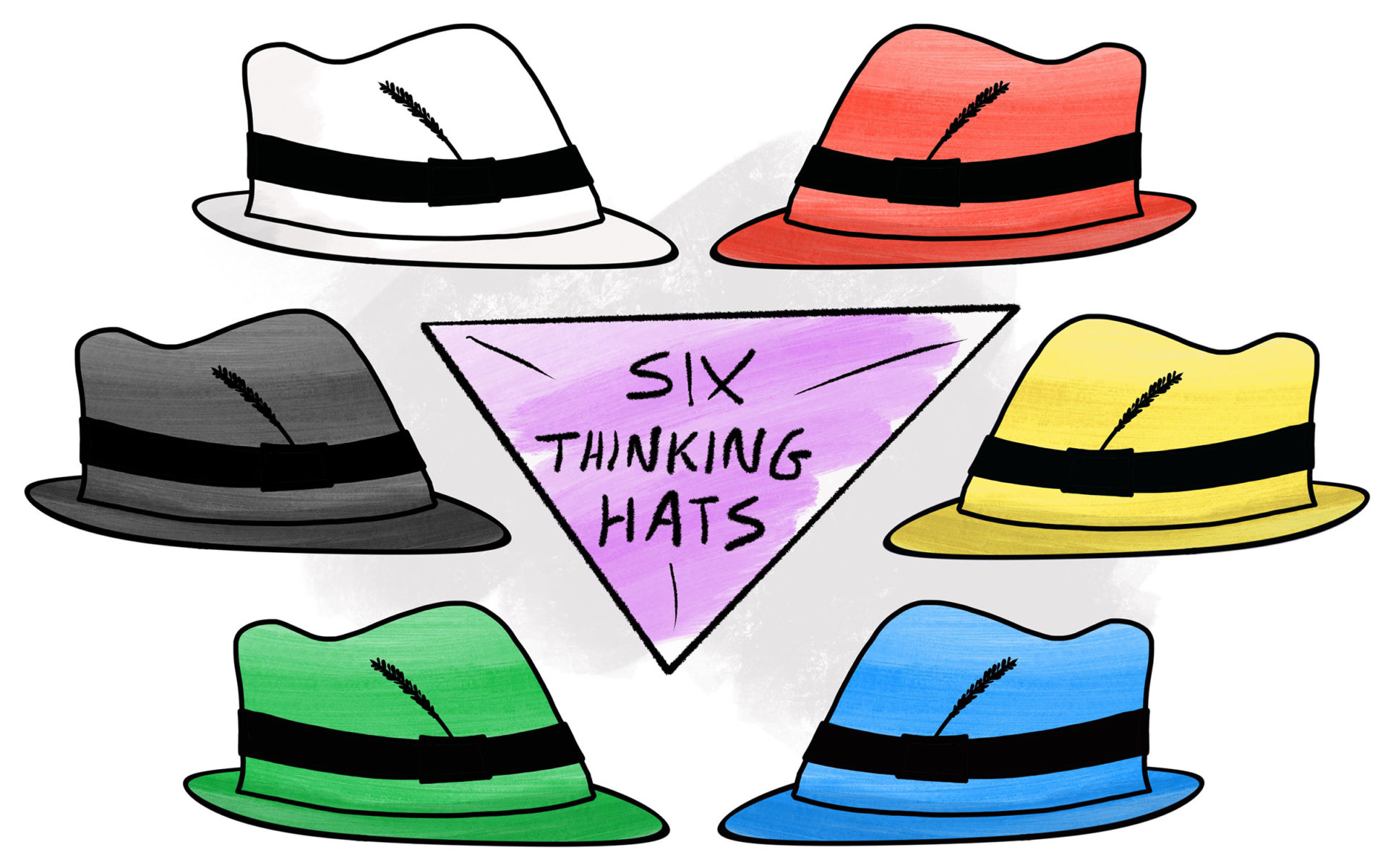

The Six Thinking Hats method may well be the most important change in human thinking for the past twenty-three hundred years.

That’s a bold statement. However, De Bono backs it up with success story after success story - from Cambodian villagers to multinational corporations; from preschoolers to researchers. This method is so powerful, de Bono explains, because “Thinking is the ultimate human resource.” - pg. xi

Improving our thinking improves every aspect of our lives.

Here's the problem - most of our thinking and communication is done on autopilot. Think of the typical meeting. One person proposes an agenda and a starting topic. Another brings up a creative concept, and someone else shoots it down. This person is always cautious, that person is always optimistic. Ideas are discussed haphazardly as they are introduced. People become confused. De Bono continues:

The main difficulty of thinking is confusion. We try to do too much at once. Emotions, information, logic, hope and creativity all crowd in on us. It is like juggling with too many balls.

What I am putting forward in this book is a very simple concept which allows a thinker to do one thing at a time. [...] The concept is that of the six thinking hats.

Thanks to a handful of ancient Greeks, the majority of Western thinking is based on argument. The methods of thought developed by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle were significant intellectual developments in their time, allowing us to determine ‘what is’ through formal structures of analysis, judgement, and argument.

However, de Bono argues that these methods are not sufficient if we wish to promote creativity and constructive thinking. He explains, “Instead of judging our way forward, we need to design our way forward. We need to be thinking about ‘what can be,’ not just about ‘what is.’” - pg. 3

In argument thinking, each person holds a different point of view and defends/promotes that position. In parallel thinking, everyone looks at the problem from each point of view in turn until all perspectives have been covered.

What are these perspectives? The Six Thinking Hats.

The hats are symbols for different directions of thinking. The system gamifies the process of looking at topics from different directions. Each person’s creativity can be used to attack a problem from all angles, rather than defending one position. Competitive people can show off through their adaptability, rather than by beating down other ideas. Meetings take less time and produce more results. Everyone wins.

Each hat has a color - white, red, black, yellow, green, and blue - and each color represents a direction of thinking.

White hat - Information, facts and figures

Red hat - Emotions and reactions

Black hat - Cautious and careful

Yellow hat - Optimism and positive thinking

Green hat - Creativity and new ideas

Blue hat - Organization and oversight

The white hat is for information, facts and figures. It provides neutral reports without argument or opinion. It differentiates between proven facts and anecdotal facts. It asks questions and determines what information is missing or needed.

The red hat is for emotions, reactions, and intuitions. It allows people to state their feelings without needing to justify them. Red hats are useful for assessing the feelings and emotions of the group independent of the facts.

Note: red hat thinking is the opposite of white hat thinking.

The black hat is cautious and careful. It helps us avoid mistakes. It points out potential weaknesses and downsides. What could go wrong? The black hat is not a justification for argument - it is merely for putting these potential downsides on the table for consideration. Note: due to negativity bias, it is easy to overdo black hat thinking. Be careful.

The yellow hat is deliberately optimistic. It identifies benefits and possibilities, and highlights what is valuable. Yellow hat thinking is constructive rather than emotional.

Note: yellow hat thinking is the opposite of black hat thinking.

The green hat is for creativity and new ideas. It allows everyone to make a creative effort and propose novel solutions. It discovers new courses of action. Ideas are documented but not judged. Creative techniques such as provocation and lateral thinking may be used.

The blue hat is for organization. It introduces agendas, keeps discipline, and announces the sequence of hats to be used. It defines problems and objectives. At the end of a session, a blue hat is used to summarize outcomes and establish next steps.

The hats may be used individually to request a certain kind of thinking, or they may be used in a predefined sequence to explore a subject or solve a problem.

The names of the hats are a useful proxy for their function. It is less offensive to ask someone to ‘take off their red hat’ than to ‘stop being emotional.’ You can also say, “Let’s have some green hat here” if you would like to generate creative ideas.

The hats may be used in any order, but a session should always start and end with a blue hat. The first blue hat is used to define what the session is for, establish any needed background, and determine what sequence of hats to use to accomplish the desired objective. The last blue hat is used to summarize what has been accomplished and what should be done moving forward.

You can use sequences of hats strategically. For example, if a meeting is an emotional one, a red hat may be called after the first blue hat to allow people to get these emotions out. If the topic is not emotional, a white hat may be a better place to start to allow all the facts to be presented first. You might use a yellow > black > green sequence for creative problem-solving; listing the benefits first can help motivate the problem-solving later.

It is worth noting that the thinking hats method is also useful outside of meetings. You can use it by yourself to help clarify your thoughts around an important decision. Recognizing which hat you are currently currently using can remind you to consider the other perspectives as well.

Of course, this is just skimming the surface - in the book, De Bono goes into great detail on the effective use of each hat, and provides strategies on how to sequence the hats for different objectives. Many of his examples are quite entertaining. The book is short, well-written, and full of ideas. Meetings will never be the same again!

There are many books that can teach you how to write better. This one goes beyond - it is about becoming a writer.

Don't let the subtitle (A Book of Aid and Comfort) or the cheery Christmas-colored cover fool you. This book offers serious insights from two serious writers - who also happened to be married to each other. As such, it offers perspectives on both being a writer and on working with one.

Isaac Asimov was by far the most prolific of the two, but the book was primarily written by Janet. Isaac's prolificity must be taken with a grain of salt, as he was clearly an outlier in both the reading ("I can read upside down as easily as right side up." - pg. 96) and writing arenas. Therefore, Janet's contribution offers a common-sense viewpoint that the average reader (and writer) can appreciate.

The first third of the book is devoted to 'coping' and contains a high density of tactical writing advice - ranging from the general ("Try to have more than one writing project going" - pg. 29) to the specific: "Readers don't notice the word "said" but other words intrude upon the smooth transfer of dialogue from the page to the reader's mind." - pg. 18

Next, we have chapters on dealing with editors and critics. Some of the strategies suggested involve a fair bit of 'cathartic vocalization':

HOW TO REACT WHEN REJECTED BY AN EDITOR

First remember George Scither's rule: "We don't reject writers; we reject pieces of paper with typing on them."

Then scream a little.

... Most writers kick and scream and there isn't any reason why you shouldn't either, if it makes you feel better. However, once you are quite done with the kicking and screaming, sit down and reread the story in the light of anything [the editor] may have told you and see if you can find out what's wrong, how to correct that wrong, and how to avoid that wrong in the future. If the rejection teaches you something, you may in the long run have gained more from it than from a too-easy acceptance of a flawed story.

Don't stay mad and decide you are the victim of incompetence and stupidity. If you do, you'll learn nothing and you'll never become a writer.

The Asimov Method of Reacting to Adverse Criticism:

Be sure to follow this sequence precisely, and never leave out number 5.

If you're concerned that the prevalence of video will leave writers in the occupational dust, Isaac includes an amusing essay on the utility of the book vs. the videocassette tape. I wonder what he would have thought of YouTube!

The final third of the book gives specific advice on writing non-fiction, fiction, specialized fiction, and children's books. At the very end, there is a list of books which constitutes the Asimov's 'working library' - both reference volumes and books to be 'reread frequently' for 'exposure to good writing'.

Interspersed throughout are humorous cartoons by Sidney Harris and relevant quotations offering perspectives from a wide variety of other writers.

The majority of the book is as timeless as writing itself (just ask Sidney Harris's cartoon cavemen). However, I wonder how Isaac - who died in 1992 - would have navigated the abundance of writing channels that exist today. He viewed editors as a necessary evil - sometimes helpful but often burdensome. Nowadays, self-publishing has removed editors from their traditional role as gatekeepers of the printing presses. How to Enjoy Writing was published in 1987; the term 'weblog' (later shortened to 'blog') was coined ten years later in 1997. Writers can now 'publish' with the click of a button.

Despite these technological advances, however, the central act of writing - communicating ideas through words - remains. Somewhere, someone still has to make up their mind to commit an 'act of authorship' and write something. And with the help of this book, they may even enjoy it.

We can readily understand many of the implications of illiteracy - but what about a widespread unfamiliarity with mathematics? Now that most of use have a smartphone calculator in our pocket, do we really need to have an intuitive grasp of mathematical concepts? In Innumeracy, John Allen Paulos explores the growing problem of mathematical illiteracy and its consequences.

The book is filled with 'brain teasers' - scenarios which look straightforward, but can be deceptive if not analyzed properly. You will find nuggets of information on calculating probabilities, rigging card games, conducting polls, debunking pseudoscience, and interpreting statistics. These are both entertaining and educational. For example:

When the leaders of eight Western countries get together for the important business of a summit meeting - having their joint picture taken - there are 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 40,320 different ways in which they can be lined up. Why?

Out of these 40,320 different ways, in how many would President Reagan and Prime Minister Thatcher be standing next to each other? To answer this, assume that Reagan and Thatcher are placed in a large burlap bag. These seven entities (the six remaining leaders and the bag) can be lined up in 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 5,040 ways (invoking the multiplication principle once again).

This number must then be multiplied by two since, once Reagan and Thatcher are removed from the bag, we have a choice as to which one of the two adjacently placed leaders should be placed first. There are thus 10,080 ways for the leaders to line up in which Reagan and Thatcher are standing next to each other.

Hence, if the leaders were randomly lined up, the probability that these two would be standing next to each other is 10,080/40,320 = 1/4.

Following along, you can calculate combinations of Mozart waltzes, potential poker hands, and the probability that your lungs contain a molecule that was part of Julius Caesar's last breath. You'll learn to decipher stock market scams, calculate distributions of birthdays in a random crowd, and choose a potential spouse the 'statistical way.'

The back cover claims that "Innumeracy lets us know what we're missing, and how we can do something about it." It certainly delivers on the first part of the promise - however, I found the second to be a little under-represented. To be clear, throughout the book each example of what not to do was followed by an example of what to do - how to properly calculate this probability, or conduct that survey - and perhaps these tactical suggestions meet the author's promise. However, I would have appreciated more data-driven suggestions on what to do about the problem at large. At times, the book also felt rather like a rant, and could have used more structure.

In the conclusion, Paulos mentions that although he is certainly "distressed by a society which depends so completely on mathematics and science and yet seems so indifferent to the innumeracy and scientific illiteracy of so many of its citizens…" the book was not motivated by anger. Instead, he explains, "The desire to arouse a sense of numerical proportion and an appreciation for the irreducibly probabilistic nature of life - this, rather than anger, was the primary motivation for the book."

Having written the playbook on the subject, Nir Eyal knows all about ‘engaging’ technology. Yes, he is the author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, the mythical yellow book that’s passed about with reverence at tech/social media companies. The same companies that, coincidentally, seem to occupy so much of our time and attention now.

He had good intentions - Hooked was written in an effort to help startups and socially concerned companies reach their users with the same effectiveness as the tech giants.

Since then, however, the problem has only gotten worse. It’s become the norm to spend hours every day endlessly scrolling on social media. It seems that the tech companies have hacked our biology and made products so addictive that they’re now integral parts of our lives. 20% of people in one survey would rather go without shoes than their phone.

Ironically, Nir eventually got ‘hooked’ himself. That’s why he decided to write another book. Why?

We are much more powerful than any of the tech giants. As an industry insider, I know their Achilles’ heel - and soon you will too.

The good news is that we have the unique ability to adapt to such threats. We can take steps right now to retrain and regain our brains. To be blunt, what other choice do we have? We don’t have time to wait for regulators to do something, and if you hold your breath waiting for corporations to make their products less distracting, well, you’re going to suffocate.

Indistractable is a guide to help you take control of your attention and focus on what matters.

Nir realized he had a problem when he noticed he was missing out on opportunities to spend quality time with his young daughter. He was getting distracted, and she wasn’t getting any younger. He knew something had to change.

First, he tried removing technology - he bought a flip phone, subscribed to a print newspaper, and did his writing on a word processor without internet access. He found himself still getting distracted - by books.

Somehow, I kept getting distracted, even without the tech that I thought was the source of the problem… Removing online technology didn’t work. I’d just replaced one distraction with another.

He knew what he had to do. He started researching this book.

Logophiles beware - Eyal starts off by redefining the word traction to mean the opposite of distraction: “We can think of traction as the actions that draw us toward what we want in life” - pg. 12

Furthermore, this is also one of those books that seeks to coin a word - namely, Indistractable. Just thought I'd give a fair warning.

Nir’s first key discovery was that our actions are motivated by discomfort.

Simply put, the drive to relieve discomfort is the root cause of all our behavior, while everything else is a proximate cause.

We may blame our environment for distracting us, but the core reason is often something within ourselves. Unless we acknowledge this, the source of our distractions will just seem to be a shape-shifting phantom embodied by different objects in our environment. We blame proximate causes like our phone - or a book - for distracting us, but the root cause is our own discomfort.

What discomfort?

It could be many things - stress about work or a relationship, anxiety about money, or even boredom. Ultimately, distractions are a way to avoid paying attention to uncomfortable areas in our lives. As Nir says,

Only by understanding our pain can we begin to control it and find better ways to deal with negative urges.

All right. If distraction is just a result of internal discomfort, can’t we just crank up our willpower and power through it? Not quite. In fact, “An endless cycle of resisting, ruminating, and finally giving in to the desire perpetuates the cycle and quite possibly drives many of our unwanted behaviors.” - pg. 34

It turns out that forcing ourselves to abstain from negative thoughts makes the pressure to relapse even stronger. More distraction. So, how do we change? By changing our thoughts themselves.

The first step is to pay attention to the internal trigger we feel before getting distracted.

Look for the discomfort that precedes the distraction, focusing in on the internal trigger.

Write down the details - what you were doing, what you felt, and the time of day. Comment on your feelings and behavior like a dispassionate observer, just documenting what you see. Note: the book and downloadable workbook both include a ‘Distraction Tracker’ that makes this easy.

Once you’ve observed a pattern, explore what you feel immediately prior to getting distracted. Spotting this feeling before giving in to distraction will help to break the cycle. Focusing on the internal trigger instead of the external distraction will help us become more aware.

Now that we know how to spot internal triggers, the next step is to change the nature of our task to be more engaging.

We can use the same neural hardwiring that keeps us hooked to media to keep us engaged in an otherwise unpleasant task.

That’s right. We’re going to turn our work into a game.

Intermittent rewards - a staple of social media psychology - are a powerful way to increase our engagement with our work. Find ways to compete with yourself. Try to break a previous record, or find a new and novel way to complete a task. Searching for novelty forces us to focus. As Nir says, “Fun is looking for the variability in something other people don’t notice. It’s breaking through the boredom and monotony to discover its hidden beauty.” - pg. 43

Now that we’ve spotted our triggers and made our task more fun, let’s take another look at willpower.

One of the most pervasive bits of folk psychology is the belief that self-control is limited - that, by the nature of our temperament, we only have so much willpower available to us. Furthermore, the thinking goes, we are liable to run out of willpower when we exert ourselves. Psychologists have a name for this phenomenon: ego depletion.

It makes sense. You work hard at something, and eventually, you get tired. You’re more likely to get distracted, more likely to make bad decisions, and… it turns out this line of thinking is wrong. Referencing a study by Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, Nir says, “People who did not see willpower as a finite resource did not show signs of ego depletion.” - pg. 46

It turns out that your limiting factor is not your lack of willpower, but rather your belief that willpower is a limiting factor. Changing our mindset allows us to tap into these stores of willpower and stay focused.

Part of eliminating the pull of distractions is knowing how you actually want to spend your time. Having a plan for your day is a powerful buttress against distractions.

You can’t call something a distraction unless you know what it’s distracting you from.

Nir recommends a technique known as ‘timeboxing.’ First determine how much time you want to spend on each domain of your life - work, family, health, etc. - and then block off time on your calendar appropriately. “Keeping a timeboxed schedule is the only way to know if you’re distracted. If you’re not spending your time doing what you’d planned, you’re off track.” - pg. 57

Having a plan for how you want to spend your time also allows you to go back later and review how you actually did spend your time. This can offer more insights, revealing additional ways you can improve.

After observing how you’re spending your time, you’ll probably want to make some changes. Where should you start?

We can start by prioritizing and timeboxing ‘you’ time. At a basic level, we need time in our schedules for sleep, hygiene, and proper nourishment. [...]

With your body and mind strong, you will also be much more likely to follow through on your promises.

Set aside enough time for proper nutrition, exercise, and sleep. These will have compounding effects as you continue to tackle other areas.

Remember that your objective is to spend your time correctly, rather than worrying about outcomes. Nir reminds us, “The one thing we control is the time we put into a task.” - pg. 64

Having elaborated on these principles in much greater detail than we have here, Nir then proceeds to application. The book offers tactical advice on applying these principles to specific communication channels and devices, including email, group chat, computers, phones, and social media. Two of my favorites are:

Nir offers specific tips on using pacts to make distraction difficult, expensive, or downright impossible. These are categorized by:

Finally, Nir concludes with specific sections filled with actionable advice on creating indistractable workplaces, raising indistractable children, and having indistractable relationships.

Neologisms aside, I found Indistractible to be an actionable guide to reclaiming attention for the things that matter. Much of the information is similar to other popular habit-change literature, but this does not diminish from its utility here.

Isaac Asimov was one of the 'big three' science fiction writers of the last century, along with Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein. As one of the most prolific writers of our time, his life is worthy of study. While best known for his science fiction, primarily the Foundation and Robot series, he also wrote widely on a variety of nonfiction subjects - producing books ranging in topic from history to technology, physics to biology, and beyond. No matter the subject, his writing is generally accessible and engaging.

In addition to his books and stories, he wrote science columns for several publications and maintained a copious correspondence, writing an estimated 90,000 letters in his lifetime. All this is documented in I. Asimov - his learning and development, adventures and misadventures, the stories behind his numerous books, and memories of his many colorful associates.

Rather than following a strictly linear time format, the book is presented as a series of short chapters or essays on various topics. These are introduced chronologically, and so the reader still follows the progression of Asimov's life. However, each topic may be read independently, as it is generally rounded out by the inclusion of additional contextual information. This means the book is easy to read in small portions, and can also be used as a handy topical reference.

By contrast, Asimov's earlier autobiographies are written in the usual chronological manner, and are much longer - although at 552 pages and 235,000 words, I. Asimov is certainly no joke. Always prolific, Asimov wrote this book in 125 days.

The book concludes with an epilogue from Janet, Asimov's second wife, and a catalogue of his published books. He produced over 500 books, both fiction and nonfiction, so the list is quite substantial.

As with other Asimov books, this one is a page-turner. It is easy to get immersed in his simple, conversational writing and lose track of time - evidence that Asimov was, in fact, one of our great explainers.